Isla Vista: Then and Now

The Isla Vista of yesterday.

Anisq’ Oyo’ Park 1997

In 1956, Isla Vista contained a population of 356. Many were students attending the newly opened university.

Stairs leading to Sands Beach 1997

Photo Credit

Del Playa 1950’s

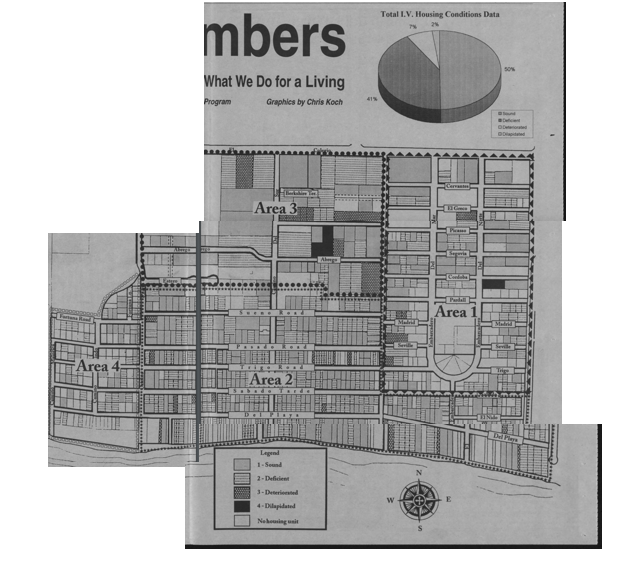

Isla Vista is an unincorporated city. A consequence of this is land developers do not face the same building regulations they normally would.

Building integrity report 1997

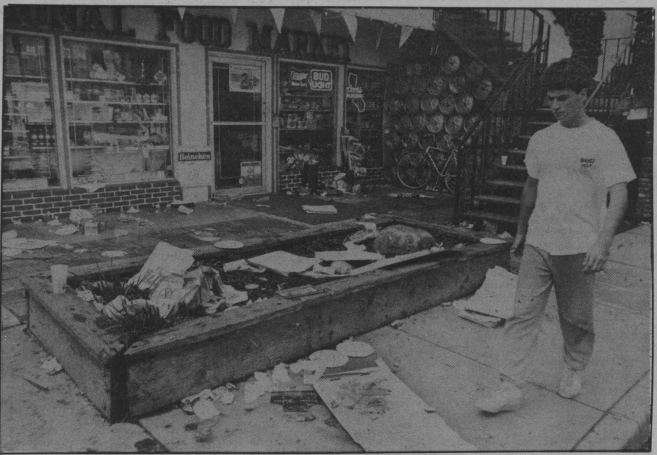

In the 1980’s, Halloween became a huge social gathering, drawing crowds of thousands to party for the weekend.

Destruction after Halloween 1987

Despite efforts to combat the impact of days like Halloween, Isla Vista remains permanently scarred.

This damage has only been amplified by the continuation of massive partying.

IV beach 2009

Although Floatopia has since been banned, the event of nearly 12,000 beachgoers has forever impacted the nature in IV.

Streets of IV during Floatopia 2009

One day, months of destruction.

Floatopia 2009

With all the students cramped into the area, the streets of Isla Vista are filled with cars and trash. *

El Nido Lane 2019

Isla Vista now has a population of more than 27k and is continuing to build. The population density is 14,857 people per square mile, making it one of the most densely populated locations in California. *

IV from above 2019

Picture captured recently of new technology decaying into the ocean. Isla Vista is still plagued by litter even with efforts to minimize ecological damage. *

Sands Beach 2019

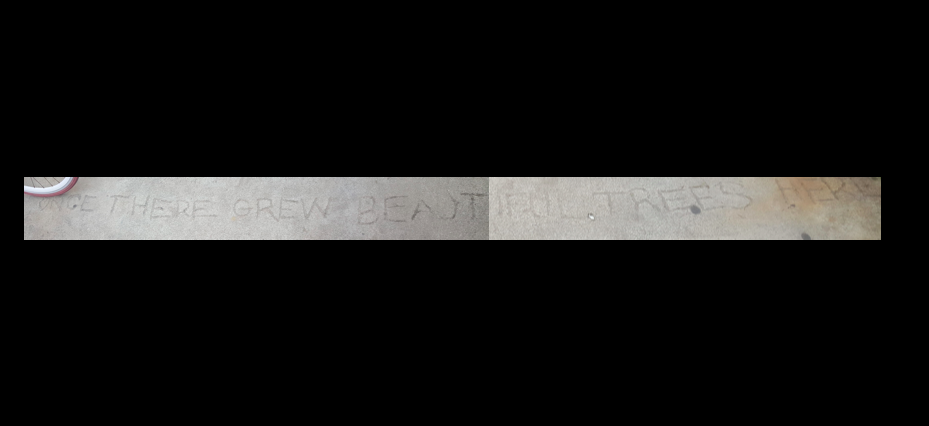

“Once there grew beautiful trees here”

A reminder of what Isla Vista has lost over the years of continuing development and urbanization. *

6645 Del Playa 2019

Aerial shots of Isla Vista over time.

1956

1971

2015

Click here to see a side-by-side juxtaposition of Isla Vista in 1956 and 2015.

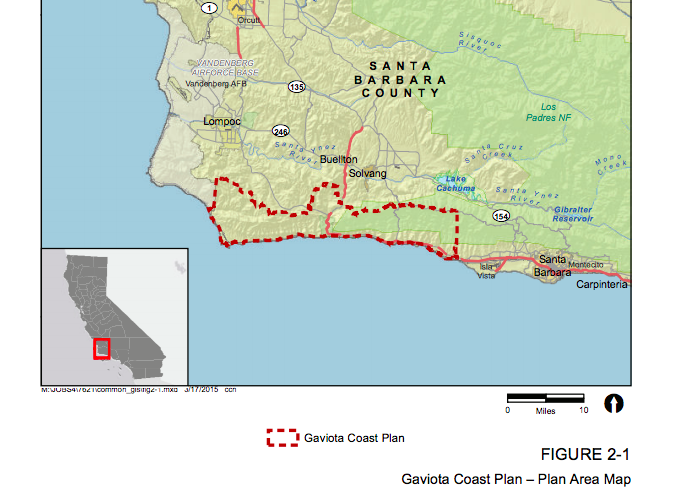

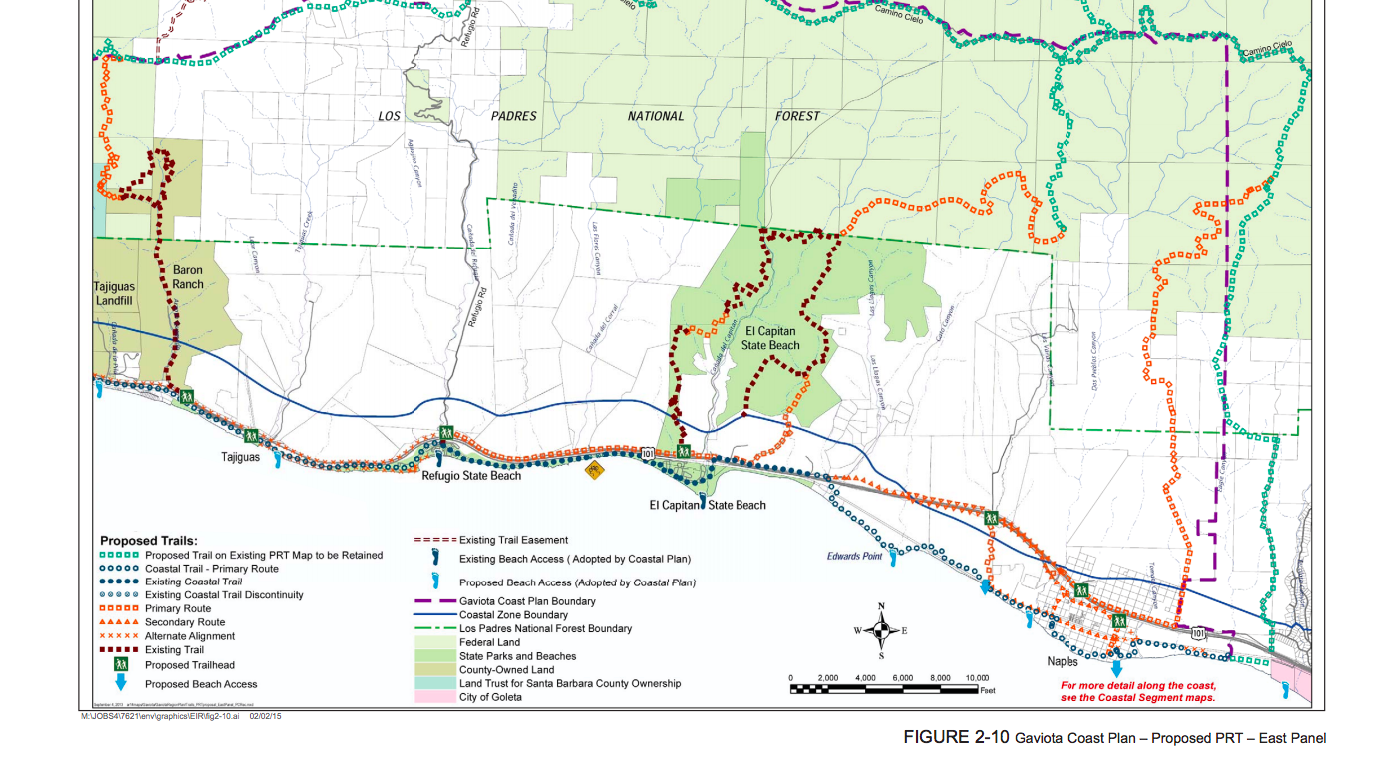

From the aerial shots alone, the extreme urbanization Isla Vista has undergone in the last sixty years makes the area almost unrecognizable when compared to what it used to be. As demonstrated through the stark changes that Isla Vista has endured over the years, the expansion and growth of UCSB have forever altered the environment and nature that once existed there. Although the results of urbanization are irreversible, the Gaviota Coast provides an interesting opportunity to imagine what Isla Vista could have been. Just north of Goleta, the Gaviota Coast is a 76 mile stretch of undeveloped land, the last of its kind in all of Southern California. Bordered by the Santa Ynez Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, the corridor of coastline is home to a unique landscape of rural beaches, remote farms, and five state and county recreational parks.

Click the video below to listen to the sounds of Gaviota.

As we examine the current state of Gaviota, we have the opportunity to travel into the past and compile an idea of what Isla Vista looked like before it became an urbanized college town. Additionally, we have the unique opportunity to visualize how the landscape of Isla Vista would look today, had UCSB never been founded. In order to create a complete description of Gaviota, it is also important to examine the factors that led the nature in Gaviota and Isla Vista to deviate so drastically. By describing the history of the area and why it has remained undeveloped, we will be able to envision the unsettled Isla Vista of the past, as well as what it could have looked like today.

Missions to Ranches

Although archaeological evidence suggests human habitation of the area began over 9,000 years ago, Gaviota, as we know it today, was first utilized for organized agriculture during the Spanish Missions Period in the late 18th century. In the 1780’s Missions La Purísima and Santa Barbara were founded, thus including Gaviota in the mission lands. When the Missions period ended in 1834, land in Gaviota was distributed to prominent local families by the Mexican government. By 1870, drought had driven most of the Mexican ranchers to sell their land to others, such as the Dibblee-Cooper-Hollister consortium. Shortly after this shift in ownership, oil development began at the refinery at Alcatraz Landing near Gaviota. Although a portion of the area was used as a prisoner of war camp during World War II, the land was once again dedicated to agriculture after the war.

The Battles

Today, much of the beautiful sprawling lands of Gaviota are privately owned by families whose acres have been inherited over generations. Recently, these landowners have been fighting to open up their private ranches and farms with their serene and breathtaking views to limited public access through the creation of tours and hiking trails. As discussed in the Coastal News Service article “Beach Fans Cleared to Fight Enclave for Coastal Access,” public access advocates are currently working with the Gaviota Coastal Trail Alliance and the State Coastal Conservancy against the Hollister Ranch Owners Association to open up the coasts to responsible public access.

“I find it offensive the idea that by allowing the public access to your pristine beach that it will no longer be pristine,” said commission chair Dayna Bochco during a December hearing. “I find it to be a subtle kind of elitism to imply you are better at protecting natural habitat.”

The Gaviota of Today

Unlike the drastic changes in urbanization that Isla Vista has faced in the past century, Gaviota remains what it always has been: natural. Home to over 77 thousand acres of agricultural land, most of the agricultural space is dedicated to cattle grazing. However, Gaviota continues to be used by new generations of farmers who utilize the advantageous climate to grow various sorts of vegetation, including avocados and citrus fruits. To this day, agriculture remains a core feature of Gaviota’s identity.

In addition to agriculture, Gaviota is known and loved for its recreational opportunities. With over 26 thousand acres of mountainous terrain, the adventures are endless. All while overlooking the sparkling blue coastline of the Pacific Ocean, any trail in the Gaviota mountains is bound to take you on an adventure. This provides great opportunities for hikers and nature enthusiasts to climb rocks, scale the rolling hills, and explore the sandstone wind caves. Within a few miles of each other, you will find vast regions of open space near the coastal bluffs, where you will notice the changes in habitat and biodiversity as you approach the coastline. This makes the unique, serene landscape that is Gaviota.

Its Wild Inhabitants

As told in a post by Odyssey Online, Gaviota is a world renowned biodiversity hotspot acting as a sanctuary for countless wildlife species. This includes black bears, mountain lions, owls, and golden eagles, with marine species such as dolphins and gray whales also living right off of its coast.

This photograph of a local Gaviota mountain lion was taken from Tom Modugno’s post.

Much of its wild residents have alarmingly found themselves on the endangered species list, with the Snowy Plover, the California Least Tern, the California Brown Pelican, the California Condor, the California Red-legged Frog, and the Southwestern Pond Turtle being only a handful of the species who not only call the untouched coast their home, but their last resort.

The California Least Tern, the above photo being taken from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website, is currently on the endangered species list. Click here to listen to their song.

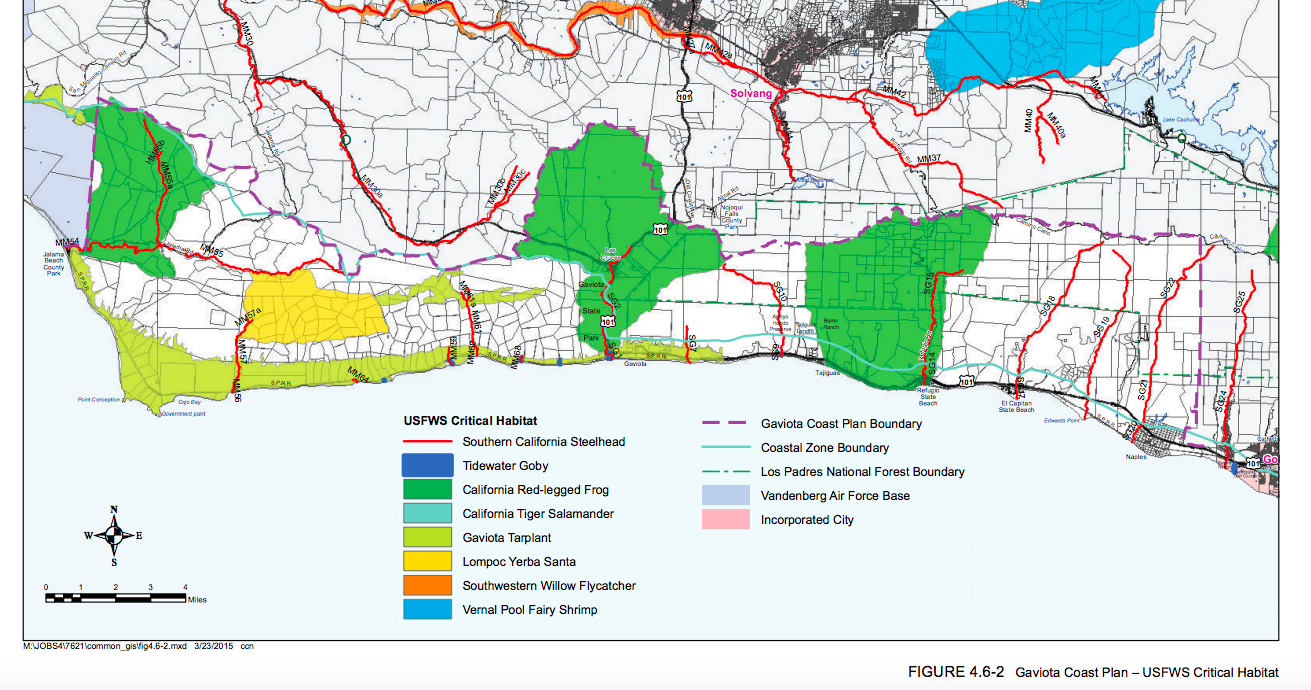

As detailed on their website, the Environmental Defense Center, or EDC, has been working alongside its partner organizations towards the permanent preservation of the Gaviota coast since 1994. In 2009, Santa Barbara County began drafting the Gaviota Coast Plan, which is a complexly thorough document that sets the framework by which future preservation and development will be handled on this precious coastline. In 2018, the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors finally voted to approve the Gaviota Coast Plan, which has been comprehensively written to ensure the area’s immaculate biological resources, rural character, and public access will be sustained for generations to come.

The above photo of a black bear was taken from an article by The Tribune, which talked about a 2018 break in by a bear into the bathroom of Nojoqui Falls Park near Gaviota. The bear ended up entering and leaving the restroom without human intervention. Park host Kathleen Ricci commented that the experience was exciting, but the bear didn’t clean up the mess he left behind.

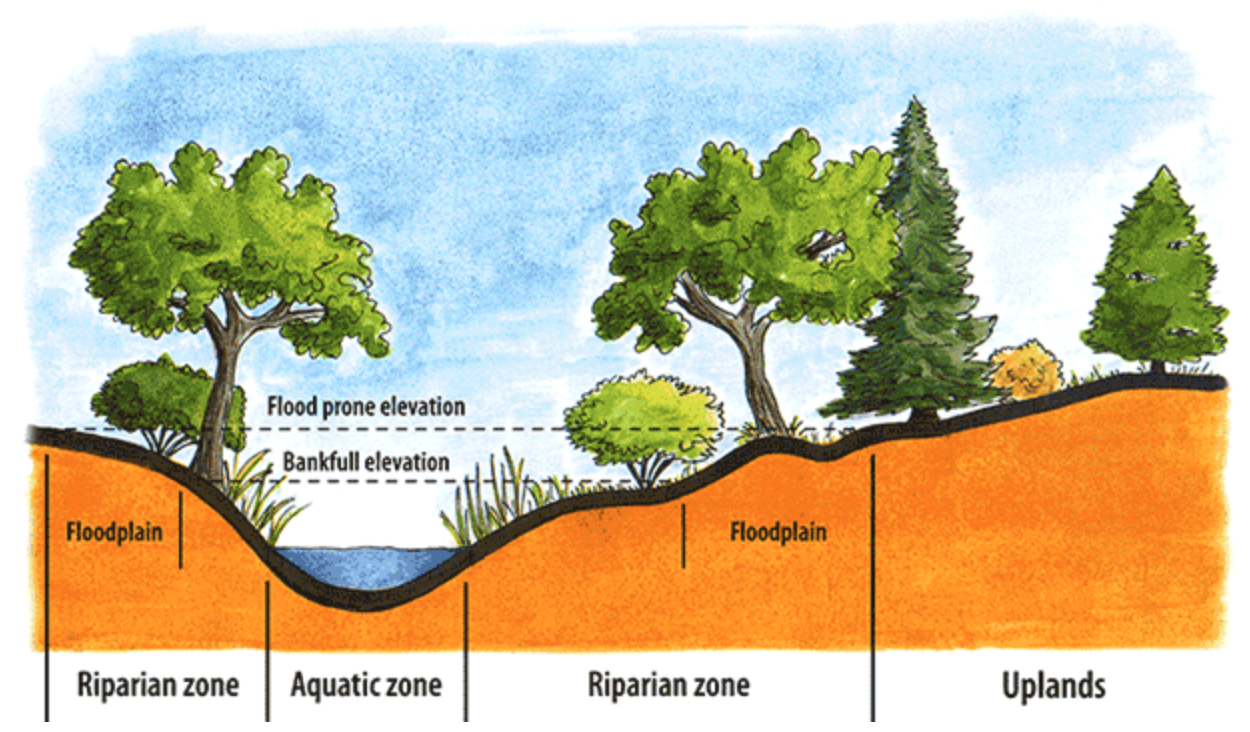

Similar to the endangered wildlife in the area, the riparian zone in Gaviota is one of only a few of its kind left in California, as the state has lost 95% of its riparian zones. Displacement would spell out certain extinction for animals such as the banana slug and California newt, whose species cannot afford to lose yet another safe haven to human development. The tide pools along its coast are also home to around 1,000 plant and animal species, with the nearby salt marshes providing shelter to over 100 bird species who have made the wetlands their lifelong residence.

A visualization of a riparian zone, which are often alluded to as the “green ribbons of life” along waterways such as rivers.

The Pacific Pond Turtle, the above photos being taken at Hollister Ranch, is currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to habitat destruction. Habitat for this species is being protected and preserved by Hollister Ranch owners in Gaviota, who named these three turtles Drake, Anita, and Little Drake.

Additionally, the tidepools along its coast are home to around 1,000 plant and animal species, with the nearby salt marshes being shelter to over 100 bird species who have made the wetlands their lifelong residence.

The above photo is from a winner of the 2017 Gaviota Photo Contest under the wildlife category.

The Kashtayit State Marine Conservation Area, or SMCA, is an example of an MPA that is found in the waters adjacent to the Gaviota State Park. Marine protected areas, or MPAs, are established in order to conserve and restore wildlife in our ocean. With the passing of the 1999 California Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA), the state established a collaborative effort to create a science-based network including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and California State Parks in order to preserve ocean biodiversity and sustain marine research and recreation. As opposed to the singling out of a species in need, MPAs allow for the broader protection of entire ecosystems and contribute to making our ocean’s complex environments more resilient and healthy in the face of climate change and pollution.

The above photo was taken by Jack Elliot, found on his post “The Wondrous Orange-Bellied Newt.” As stated on CuriOdyssey, the California newt is remarkably equipped for handling sudden wildlires. In the event of one, the light coating on the newt’s skin foams and chars into a white crusty ash. This prevents its entire body from catching fire, and the foam undercoating acts as insulation to combat the heat of the flames.

Gaviota also provides a home to a local animal rehab center called Channel Islands Marine & Wildlife Institute, or CIMWI. Formerly a school ground that had been abandoned for two decades, J. J. Hollister III handed off the property to the Dovers at a reasonable price in order for them to transform it into a living, breathing facility. The Dovers’ center rescues, rehabilitates, and releases marine mammals in need of care in Ventura County year round. They are able to do this with the help of their passionate volunteers and with the aid of other Santa Barbara County animal care facilities, such as the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network and SeaWorld.

Exceptional Climate

Gaviota’s weather, which only deviates 10 degrees Fahrenheit from a year round mean of 70 degrees, is a large part of the area’s identity and what makes it such a special place. Despite inconsistent rainfall, there is still an abundance of plant life within Gaviota’s perimeters. Some of Gaviota’s rare treasures include the Bishop pine forest, tanoak forest, valley oak woodlands, in addition to native grasslands and wetlands that provide biologically diverse plant species within themselves. In fact, many of these species are native to the surrounding land, with names like the Gaviota tarplant, Lompoc yerba santa, and the Santa Ynez false lupine. While Gaviota has a lot to give, the vast majority of these plants are rare and endangered, and will require us to return the favor by preserving the land.

Gaviota’s native grasslands on the way to the wind caves*

A photo posted on tripadvisor highlighting the endangered state of Gaviota’s Bishop Pine Forest

While organizations including the South Coast Habitat Restoration (SCHR) are partnering with the Southern California Wetland Recovery project to remove invasive plant species by river banks, more awareness needs to be raised in order to keep this vision of restoration alive. Although weather and rainfall play a critical role in the longevity of these endangered species, we can do our part by understanding the importance of preserving natural reserves. We see what Isla Vista has become. In order to prevent Gaviota from suffering from the same harmful repercussions of urbanization, a positive vision of Gaviota’s future must be established.

The Future of Preservation

Existing on the same coastline less than 25 miles away from each other, Isla Vista and Gaviota have their similarities, but have become two extremely different places. In the last century, they have diverged from one another and taken two drastically different paths. In the heart of Isla Vista, it is easy to get carried away by the restaurants, retail, housing, and college culture in a way that fails to make the environment a priority. Meanwhile, Gaviota is a prime, modern day example of the feel Isla Vista has lost, and what it could have looked like without a large urban population: vast rolling hills, coastal terraces, and sanctuary to a beautiful and endangered array of wildlife. While much of Isla Vista’s ecological history has already been irreversibly written, we can use Gaviota as a role model for our future hopes of Isla Vista, in order to preserve what’s left of it. Despite the differences that make each place unique, it’s important to take a step back to enjoy the scenery and ask ourselves what we want to make of the time we still have. What will Isla Vista look like if we continue with the trend of the past couple decades? Is the trade-off between nature and urbanization truly worth it? Perhaps it’s time to return to our roots by using Gaviota as an archetype of what Isla Vista could look like if we had let it.

Looking at the land through Gaviota’s eye provides direction for Isla Vista’s future. *

Important Note: Any photo without a hyperlink to its source and captioned with an * was taken by an author of this story.